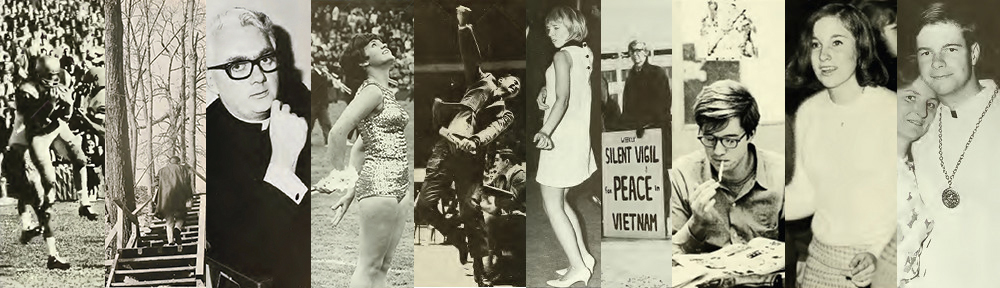

(Not exactly “us,” meaning BC students, but fellow college students of our time. The April 2, 1968, issue of Look Magazine featured a report on college student attitudes, collected from 23 editors of college newspapers around the country. Below are excerpts. Do these reflect your views at the time? Do you think BC was typical of American colleges of the day? More conservative? More liberal?)

People who think of the university years as a time of carefree joy and youthful optimism had better go back to campus for a visit. They might be surprised. Today, across the nation, a complicated sickness is eating away at the souls of many American college students. In huge educational factories, on tiny exclusive campuses, at religious schools and among the strongholds of iconoclasm, the anguish is felt. Some students seem to feel it more than others, some verbalize it articulately, while others just vaguely feel something is wrong.

[Speaking with panels of campus newspaper editors from the East, Midwest, and West] we found that the same issues dominated the discussions of all the panels: the Vietnam war, a desire for more student power, race relations in the U.S., and a nameless malaise born of the feeling among students that their personal destinies are caught up in forces they cannot influence.

Vietnam and the draft were the central issues. There is a panic on the American campus of 1968. The long-smoldering uneasiness about the U.S. role in the Vietnam war has suddenly been ignited by the Government’s February decision to end deferments for most graduate students. The senior of ’68 can temporize no longer. Come June, he stands an almost 50-50 chance of being drafted unless there is another sudden shift in the Selective Service laws.

But it is not only the world beyond the university gates that troubles today’s student. The type of learning he gets is also a source of misgivings. Many editors report a growing dissatisfaction, and tell of the rising demand for a more loosely structured curriculum, one that is more relevant to the kind of world into which the students will be emerging. Basic to this desire for education reform is the demand that university administrations give a bigger chunk of the decision-making to students themselves, including the power to discipline.

Not all students on America’s campuses share the views of the college editors on Look‘s panels. As our participants agree, most undergraduates are immersed in the day-to-day demands of academic life, are seldom in the ranks of the placard carriers no matter what the cause.

Vietnam

. . . [T]he war dominated the students’ discussion. . . . Only two students said they were in favor of current U.S. policy in Vietnam. The attitudes of the rest ranged from doubt to outright hostility. But more than policy, the talk centered on the draft, surfacing alienation, confusion and bitterness. . . . “I don’t like the war over there,” [says Notre Dame’s Pat Collins], I don’t think we should be there, but what the hell can I do?” Harvard’s Joel Kramer says: “. . . Students think about the war and what their commitment is to the United States, and whether they believe in their country’s fighting. Then they think about the draft in terms of one question: Am I going to serve in the Army? They don’t worry about whether Negroes are being drafted disproportionately, or poor people being drafted instead of rich people. There is only one question: What am I going to do when they knock on my door?”

. . . Adrienne Manns, reporting on the feeling at predominantly Negro Howard University, says, “A lot of fellows feel they shouldn’t be involved in the Army at all, under any circumstance. It has little to do with Vietnam. They don’t feel that they have a responsibility to the country because they don’t feel it’s their country, that they are considered citizens of it or respected.”

. . . The editors acknowledge that most students will not resist the draft, although they might feel strongly that the war is wrong. They are acutely aware of the penalties for open resistance.

Race

. . . Behind the war and the question of educational reform, the race issue was cited by student editors as the most talked-about topic on campus in 1968. But there was much less unanimity of attitudes. Some students thought the problems of color were easing and believed their generation would be much freer of prejudice than their parents’.

. . . But the race issue elicits feelings that some students confess are ambivalent. . . . Some editors, quizzed on their attitude toward interracial marriage, admitted they “found it troubling,” or “it bothers me,” or “I feel no shock when I see others, but I don’t think I could.” Still others said, “it doesn’t bother me in the least,” and cited interracial couples whom they knew.

For the most part, racial attitudes tended to reflect the students’ regional mores. But like everything else, race is taking a backseat to Vietnam. “The civil-rights issue is dying,” says the University of Nevada’s George Frank. “Now, the war is the most important issue because it hits those between 18 and 25. It means life or death to them.”

Education reform

While they debate the proper way to pierce the walls around many venerated traditions, a growing number of students are also questioning the kind of education being given on their campuses, and calling for innovative revisions. Some of the dissatisfaction comes from the kinds of courses in which lessons and exams are rigidly structured and in which the student’s own contribution seems minimal. “The student no longer sits and listens gullibly as he did in the 1950’s,” says George Frank. “Today, he is evaluating everything the professor says to him in the light of his own knowledge — which may have been gained in or out of the classroom.”

. . . “After four years of Harvard,” says Kramer, “you begin thinking — maybe you start in your junior year — ‘I’ve been going to lectures for four years. Is this whole system of sitting in a room with 500 other students, listening to one man talking about Jonson’s poetry, is this the meaning of education?’ ”

As might be expected, educational philosophy is being affected by religious and racial changes. Frank Quigley of Fordham, a New York Catholic university, says: “The education at Fordham and the teachings we got at grammar school in the Catholic Church are two different things. Fordham is completely detached now from the stereotypical or ghetto [Catholic] mentality. We’ve gotten out of that. But now, you’re disoriented, and there are just no more [automatic] answers.”

. . . Joel Kramer offers an explanation for the students’ growing dissatisfaction with the relevance of their education, an explanation agreed upon by many of the undergraduate editors on Look‘s panels: “This is the first generation of students that is not going to school for purely economic reasons. At Harvard, most of their parents are professionals, and the kids don’t have to go to school just to make a living. Most of them are not worried about that. They, therefore, become the first generation, I think, to look at education as education. You begin to be very critical of it because you’re more interested in what it does to your mind than in what degree or diploma it gives you when you get out.”

Sex and drugs

Among the editors of Look‘s college panels, questions about sex and drugs on campus were received with pained tolerance. Always asked about them, they have become bored. The two subjects, which have furnished juicy tidbits for general newspaper readers, seem to have settled into the warp and woof of contemporary campus life. All three panels indicated that the use of LSD and the so-called “mind-expanding” drugs has peaked in the avant garde schools and is now on the wane. Marijuana, or “pot,” however, is now a standard campus commodity, students say.

. . . On matters of sex, student editors report a groping for significant relationships, sometimes through sex. Premarital sex is more the norm, although both men and women report that, among their acquaintances, sex is reserved for one’s betrothed or steady date. In sex, as in other areas of collegiate life, there are some hang-ups.

. . . Says Stephens College’s Sue Porter: “I think there’s too much concern on NOW in the dating situation. I kind of resent the fact that when somebody calls up for a date at a girls school, the party is probably going to be an emotional stimulation — either through drinking or sex — and not where you can just talk to people, communicate, like we’re doing now.” Everything seems geared “for the moment,” she says, “because it’s been a frustrating week, this is the only change to get away from the grades, the administrators and the frustrations of a week of school. I think maybe the schools are creating this, but I think, too, that we are creating it for ourselves.”

Heroes

. . . Quizzed on current campus heroes, the student editors found it difficult to name any. Some speak wistfully of the Kennedy era as the last of the hero worshipping days.

. . . The nearest thing to heroes for many students is the Beatles. “The Beatles grew up right along with us,” says Notre Dame’s Collins. “If you take the time to go through their music, it is really neat to see how these people with all their money still manage to keep moving, to keep telling the story while we are thinking of it. They’re like the great scribes of our era.”

. . . The names of the Presidential aspirants drew little except derisive laughter from most editors. . . . With few exceptions, LBJ was scorned.

Parents

. . . Many editors spoke devotedly of their parents but confessed to an inability to communicate with them on sensitive subjects. “My father just refuses to accept the fact that things are changing, that people are thinking about new things,” says one editor. . . . A girl says, “My father is all gung ho on education, to get X degrees, regardless of whether you learn or of what it means. I could get a Ph.D. in Brothel Management, and he’d be thrilled because I have a Ph.D. My father’s a dreamer who never realized his dreams. I dream, and I intend to realize mine.”

. . . [One editor says]: “Most of our parents grew up in the Depression, and they were really hurting. They are concerned with money, status, and they’re very insecure. Most of us, on the contrary, grew up in the most abundant society the world’s ever seen. And to us, abundance and all the trappings isn’t something to work for because you have it. You’re used to it, it’s nothing. So you start getting into human values because you’ve gone beyond the security thing. And our parents just can’t understand that.”

Look‘s conclusion

. . . To an adult outsider, the present mood on some campuses may seem like an aimless nihilism, a pointless lashing out at every target within slogan range. Especially, since some of the targets are the most deeply held notions of the over-thirty folk. But the thrashing about is often the outward symptom of a highly idealistic youth in an age when realpolitik dictates the suspension of ideals; when morality is a puzzle wrapped in platitudes; and the “national interest” is invoked to novocaine obvious contradictions. Faced with decisions such as their parents did not confront, the students of ’68 must become instant Thoreaus, micro-Solomons. Predictably, confusion vies with outrage, indecision contends with despair. But under it all runs a strong desire to make a positive achievement. . . . Fordham’s Quigley says: “You begin to feel in college that you are committed to some very high ideal, at least I do, but you don’t know what to do about it. Still, you can’t just go out and on to graduate school, then into your father’s business. Commitment is the antithesis of that. And to achieve something requires work.”