About a week after activist Bill Baird had been arrested by Boston police for talking about birth control and handing out contraceptives at a Boston University appearance on April 6, 1967, The Heights carried a front-page article “Baird to talk despite friction” with an overline, “Birth Control Lecture on Monday.”

Baird had been arrested for violating Massachusetts’ “Crimes against Chastity” statute, which, among other things, prohibited the distribution of contraceptives, or even information about them, by anyone other than a physician or pharmacist and then only to married persons.

A few days following Baird’s arrest, classmate and Heights editor Mike Rahill had communicated with James McIntyre, then director of student personnel services, about an upcoming Heights-sponsored lecture on campus by Baird. Rahill requested the lecture take place in Bapst Auditorium. McIntyre, according to the article, informed Rahill of BC’s “structure” policy, under which the University “reserves the right to structure the format and prescribe conditions for certain non-university speakers.”

(To be forewarned, this post is quite Heights-centric. While, overall, the issues involved included free speech, campus rules, etc., a relatively small portion of the student body likely paid much attention to this particular episode of our years at BC.)

The Heights announced that Baird’s talk would take place on Monday, April 17, at 4 pm at “a site which had not been determined.” The Heights had told McIntyre that, if BC did not permit the lecture to take place in Bapst, Baird would speak to Heights staff in McElroy 102, the newspaper’s office, and, the article said, “Anyone interested in hearing Mr. Baird speak is invited to attend.”

Later coverage of the affair in The Heights reported that George Drury, SJ, director of university personnel services, had told the editors on Thursday, April 13, after the paper’s deadline, that Baird would be permitted to speak, but only to Heights editors and staff, not “publicly.” Fr. Drury said BC’s decision was not based on the content of Baird’s talk but because of Baird’s “irresponsible actions” at BU.

In the days, indeed hours, leading up to the Baird appearance, behind the scenes at The Heights, of which I and classmate Tom Sugrue were co-sports editors, there was more than a bit of tension. It’s difficult to remember all the details and timeline, but ultimately Baird appeared and spoke in McElroy on that Monday, the 17th, to a packed Heights office and, via speakers, to hundreds of students pressed in the hallways of McElroy’s first floor.

Earlier that Monday, Heights editors had been asked to appear before Fr. Drury. He told those of us there that proceeding with Baird’s “public” appearance would be a “serious breach of university policy.” He warned us that, if we moved ahead with the appearance, he would refer the matter to the University Conduct Committee and that possible repercussions could include suspension, revocation of financial aid, and removal from editorial position. Following that meeting, the editors met in The Heights office to vote on how to proceed.

Personally, I was flummoxed. I strongly supported our right to have Baird appear, but I had no idea how I would explain to my parents, who were funding most of my education, that I would risk suspension from school, and whatever that could mean to grad school, etc. As the vote moved around the circle of us sitting on chairs, desks, etc., I grew increasingly anxious about what I would do. I don’t remember whether editorial page editor and classmate Bob O’Neill was immediately before me or a couple of people before me, but when he said he would abstain I had my answer. I also abstained. Not my moment of highest integrity, but certainly a moment of relief.

The vote actually ended up 4-4-2, four in favor of Baird appearing (including Rahill, editor-in-chief, and classmate Gerry Shea, managing editor) four opposed (including classmates Ed Amento and Don Bouchoux), and two abstentions. The higher ranking editors had stated their votes had greater weight than those in “lesser” positions, which caused some rancor. Most of the higher weighted votes were in favor, so the motion passed.

Baird spoke for 45 minutes in the Heights office, according to the April 18 article in the Boston Globe, “Birth Control Talk Sneaked In at B.C.,“ (BG_Baird_041867), to about 350 people “most of whom had to stand in basement corridors to hear the speech over a public address system.” As Baird had promised beforehand, he did not distribute any contraceptives.

The issue of editors’ votes having different values became somewhat moot when Sugrue, who had been absent from the original vote, added his vote in favor. Tom had been visiting his home in New York City that weekend and didn’t get back to campus until after the vote. He did attend the Baird speech, however.

“No one was really pressing me to ‘go on the record,'” he recalled, “but, after thinking about it overnight and talking about it with friends, I decided I wanted to align myself with the ‘rebels,’ so to speak.”

Tom drafted a letter to Fr. Drury asking to be included among those editors facing sanctions. Before submitting it, he had the chance to talk it over with his father, a journalist. “Being a newspaperman professionally and a liberal politically (and a good dad),” Tom said, “he said it was up to me, but he supported what I planned to do.”

“That, obviously, made the decision a lot easier,” Tom added. “To be candid, I recognize that the whole decision-making process, while a difficult one, was easier for me than for others. While I said in my statement to Fr. Drury that, had I been at the editors meeting, I would have voted to proceed with the Baird speech, I don’t really know that for sure. I had the big advantage of being able to think about things overnight, consult with people, weigh the pro’s and con’s, etc., compared to others who had to make a difficult decision on the spot.”

Sugrue’s initial effort to join the other editors facing sanction was rejected by Fr. Drury on the basis of his absence from the editorial meeting. Tom even appealed to the chair of the conduct board, CBA assistant dean Christopher Flynn. Flynn, according to Sugrue, said the letter was “very nice,” but he did not think it necessary to add Sugrue to those to appear before the board. “He clearly seemed interested in tamping the whole thing down,” said Sugrue, “not expanding it.” While Flynn did not say so explicitly, Tom added, “he left me with the distinct impression that he thought the situation never should have gotten to where it was.”

The April 21 Heights reported “Editors facing sanctions in fight over Baird lecture.” The issue also contained an article about Baird’s talk itself — “Baird claims birth control laws here ‘most backward’” — rather than the administration’s response and an analysis based on an interview with Fr. Drury, “‘Catholic’ vs. ‘university.’”

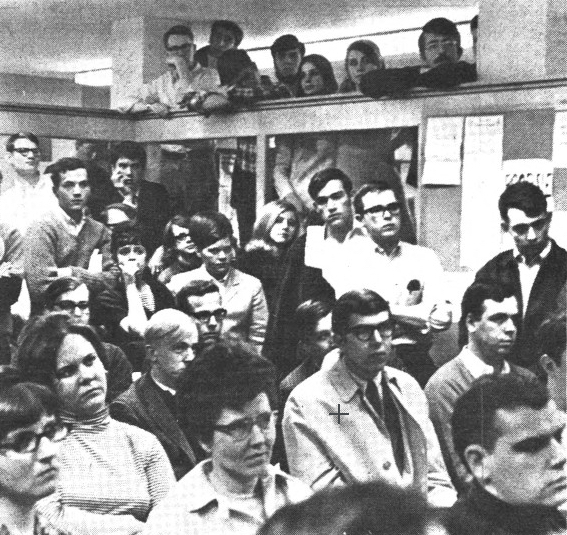

A week later, the Globe, reporting on a “two-hour closed hearing” of the conduct board on April 27 in McElroy, predicted “Mild Rebuke Likely For B.C. Editors” (BG_leniency_042867), The “tip-off” to mild, according to the Globe, came when Fr. Drury, who brought the charges, asked the board to “choose to be lenient, not severe.” Dean Flynn confirmed that inclination when he replied, “It was never the intention of this committee to disturb [the editors’] scholarship standing, the Heights, or their editorial positions.”

The Globe also reported that about 200 BC students “clogged the halls” outside the room. The students, blocked from attending, sang the Mickey Mouse song, the Globe said, and locked the doors of the room from the outside. “A priest unlocked them with a master key before the meeting ended,” said the Globe.

In the April 28 Heights, written before the board hearing took place but published the day after, the only mention of the topic is a small notice on page one that says a full story would appear in the next issue. That it did — “Conduct board to decide on editors’ fate after May 8.” But that was the last issue of the academic year. News of the final decision spread only by word of mouth until the September 11 edition of The Heights, a short four-page “orientation” issue, reported briefly that the editors were “officially reprimanded” and warned of harsher consequences if the behavior was repeated.

Bill Baird (remember him?) was out on bail from his arrest at BU when he spoke at BC. He later spent three months in the then-Charles Street Jail for violating the Commonwealth’s “Crimes against Chastity” statute. In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in Eisenstadt v. Baird (Thomas Eisenstadt was then sheriff of Suffolk County), the appeal of Baird’s conviction, that unmarried Massachusetts citizens had the same right as married persons to contraceptives and information about them.