May each year was a time of anticipation. Finals, summer vacation, summer job, maybe some travel. Of course, that last May — in 1968 — carried an extra level of excitement, suspense. It was our last one at BC.

Befitting the truncated timeframe of Mays, there were only a few issues of The Heights. Two each in May of 1965 and 1966, one each in May 1967 and 1968. Here are some of the things that happened on campus . . . and in the outside world . . . in May each of the years we were at BC. Little did we know what was to come.

1965

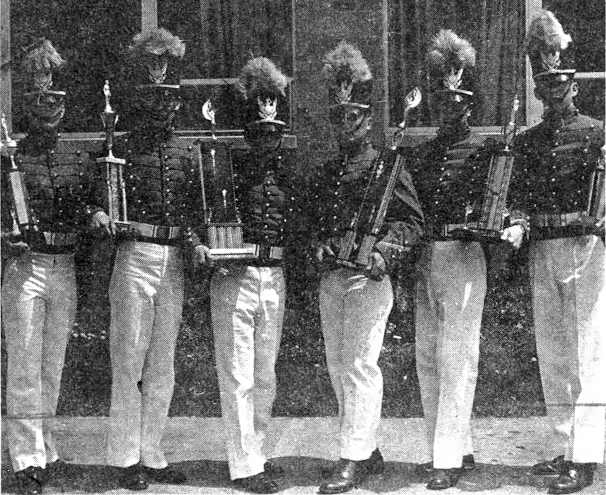

The May 7 Heights carried an article “Cadets Go Through Paces In Ft. Devens Training Day.” The day’s activities were considered a prelude to the ROTC brigade’s “summer camp.” The article referred to Fort Devens as being in “western Massachusetts.” As the installation is located just outside what is now I-495, I guess that pretty much counted as “western” to a Boston-centric writer. According to the article, those cadets overseeing the activities were “gaily attired in fatigues and ascots.”

BC ROTC on the range

On the back page, in Sports, there was a small item reporting that classmate Steve Adelman had been named to the 15-member US basketball team that would participate in the Maccabiah Games that August. The Games are a worldwide competition among Jewish athletes, held every four years in Israel.

Also, our classmates on the football team had their first competition as members of the varsity in the game the concluded spring practice. In it, “MAROONS 42, WHITES 0.” Classmates mentioned were Brendan McCarthy, Dick DeLeonardis, and Joe DiVito.

The Heights announced in its May 14 issue that “Fr. Healey, Prof. Maguire Share Heights Man of the Year Award.” Both men were faculty members in the Classics Department. Interestingly, the following year, students came back from summer break to learn Fr. Healey had been dismissed from the faculty, with no reasons announced.

Debating was a big deal back then. Page one carried coverage of the Fulton-Gargan prize debate and banquet, involving several of our classmates, though only freshmen then. “McLaughlin, Halli Cop Fulton-Gargan Prize” used a term not often used in formal debate, but reported that classmate Robert Halli had “copped” the “supreme” prize for underclassmen. Also mentioned in the article were classmates Dick Sumberg, John Riley, and Art Desrosiers.

There was an odd item on the front page as well. An “article” about ROTC . . . written in German, by “Hans Hanrahan, ROTC PIO.” I expect “DIE KINDER-SOLDATEN JA, JA, JA!” was intended as “humorous” or “satirical.” Then again, I don’t know German.

Page three reported “Revised Theology Program Announced for All Schools.” Beginning in the fall, all students, except in Evening College, would take the same series of Theology courses.

Feature writer Michael Egger gave an account of that year’s annual “panty raid” by Harvard men on Radcliffe in “PAGANS OVER THE CHARLES.”

1966

The May 6 issue announced “Theology Dept. Appoints Three New Professors.” Reflecting the changing times in theology at BC, the new faculty members included a rabbi and a woman. The woman was Mary Daly, who later became the source of much controversy. A self-described “radical lesbian feminist,” she was given a “terminal contract” by BC in 1969 following the publication of her first book, “The Church and the Second Sex,” which meant she would not return to the faculty after that semester. A petition signed by 2,500 BC students and protests led to her contract renewal and later tenure. In 1999, following controversy at her refusal to allow men into her classes, she retired rather than change her policy.

The May 6 issue announced “Theology Dept. Appoints Three New Professors.” Reflecting the changing times in theology at BC, the new faculty members included a rabbi and a woman. The woman was Mary Daly, who later became the source of much controversy. A self-described “radical lesbian feminist,” she was given a “terminal contract” by BC in 1969 following the publication of her first book, “The Church and the Second Sex,” which meant she would not return to the faculty after that semester. A petition signed by 2,500 BC students and protests led to her contract renewal and later tenure. In 1999, following controversy at her refusal to allow men into her classes, she retired rather than change her policy.

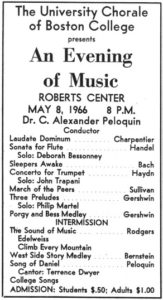

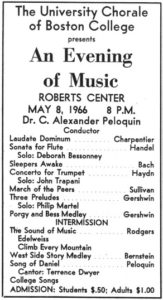

Ad in May 13, 1966, Heights

The following week, page one announced “Frs. Leonard & Flanagan ‘Men of the Year.’” William Leonard, SJ, was chairman of the Theology Department and Joseph Flanagan, SJ, headed up the Philosophy Department. Both were cited for their leadership of changes in both departments.

Co-sports editor (with classmate Reid Oslin) and classmate Dan Connolly penned a column “STUDENTS?” which he chastised the too many BC student-athletes of our day who acted boorishly. “It doesn’t take that much effort to pick them out,” he said. “Shoving in line ahead of people who have been waiting for considerable time, shuffling across campus in their sweater-tie-levis with the wingtip shoes, refusing to bus their trays in the caf, or meandering on the Upper Campus in shower thongs and gray ‘T’ shirts.” And this from a sports editor!

1967

The Junior Class (that was us) sponsored a concert by Ray Charles on Saturday, May 6, according to an item in The Heights of May 5, the only edition of the month. The performance was at 2 pm in Roberts Center. Three bucks a ticket. I went. Probably with a date. What the heck — blow $6. I remember very much enjoying the Raelettes.

Classmate and Heights editor-in-chief Mike Rahill offered a review of 1966-67 in “What follows ‘in loco parentis’?” “Looking at the most dramatic elements,” Rahill began, “it [the year] began badly and ended worse.”

“Senate commends ‘unsung’ juniors” mentioned several classmates: Roy Dado, Ed Hattauer, Mike Mastronardi, Mike Rahill, John Riley, Joe Ryan, and Jim Stanton. This was the A&S Student Senate and they commended the group “for understanding (sic), and for the most part, unheralded work on behalf of the class of 1968. . . .” I’m gonna guess they meant “outstanding” work and I’m also going to assume they thought us sports writers/editors among the class were already heralded sufficiently.

A letter from Prof. Vincent McCrossen (more about him in a coming post) — “About the anarchists” — described what he considered a lot of “fuzzy thinking” surrounding what he described as the Heights-editors-Baird case. “As a non-extremist myself . . . ,” he said, “I take my stand unconditionally on the side of Fr. Drury but equally unconditionally plead for non-punishment of The Heights editors.”

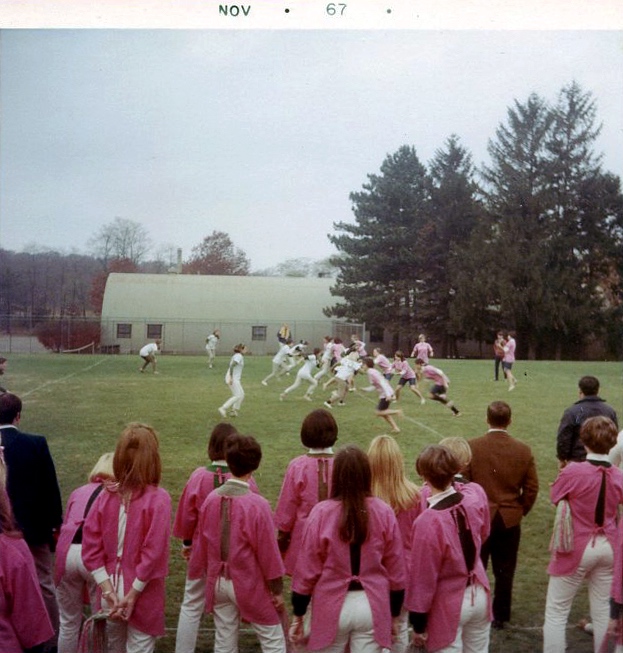

Junior Show 1967

Features editor John Golenski reviewed the Junior Show (that’s us again) and really liked it. In “You did succeed,” he said, “In performance, competence and professionality, ‘How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying’ attained near perfection.” Classmates praised in the review included Chip Auker, Jane Larchez, Richard DeRusso, Alan Borsari, and Elaine Nelson for performances onstage; Michele Lentine, John Trapani, and Phil Martel for backstage work; and especially Phil di Belardino, director.

The first annual Heights Athlete of the Year Award went to Billy Evans, sophomore guard on the basketball team. In “EVANS ATHLETE OF THE YEAR,” the article noted that, in a vote of the sports staff, Evans garnered one vote more than classmate Jim Kavanagh, star on both the football and track teams. The Heights still has this annual award. Except, for many years, awards have gone to the male and female athletes of the year.

1968

The May 7 Heights led off with a review of the presidency of Michael Walsh, SJ, who had announced his retirement in February. “Fr. Walsh completes decade as president” was as much tribute as news article. It concluded with, “He has given us the right to be proud, not only of past accomplishment but of our opportunities for future greatness.”

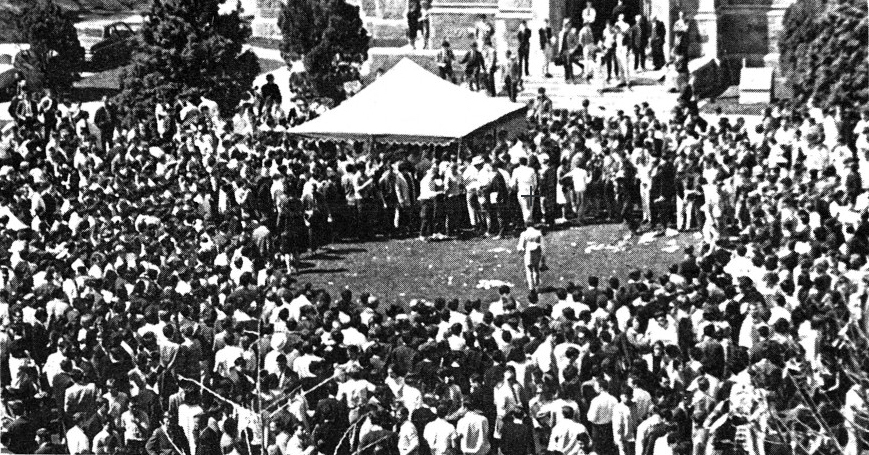

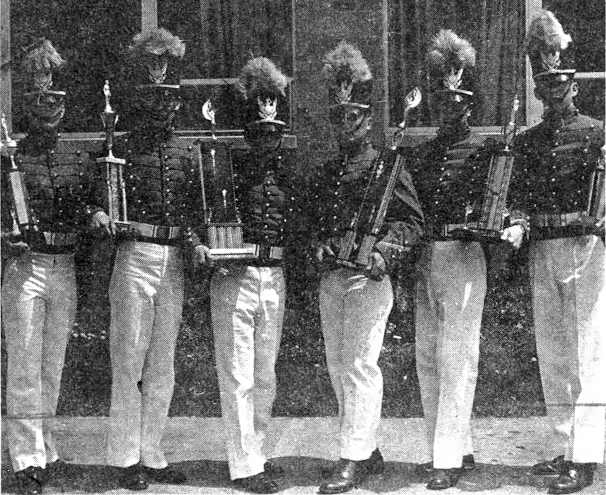

Members of the Lewis Drill Team display trophies, May 1968

Also on page one, “HEW examines enrollment of Boston Negroes at BC.” The then-US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, the article said, spent two days on campus interviewing top administrators as part of a nationwide study of how colleges were dispensing federal funds in light of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. An HEW official told the Boston Globe that BC was chosen as a representative university in a large urban area. The article noted that enrollment of African-Americans at BC at the time was less than one percent.

The “news briefs” on page two contained a brief item announcing an upcoming meeting of the “University Committee Against Racism.” The meeting was to discuss summer programs, racism in the university, and racism in the university’s hiring practices.”

“Little progress made in women’s dorms; food quality remains major complaint” pretty much says it. While the page one article about Fr. Walsh contained praise, this article concluded with “The Council of Resident Women feels that Fr. Walsh has tried very little to help the situation.”

There was another year in review. Its tone might be inferred from the title — “The slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe.”

Usually, “The Heights Man of the Year” was selected by an advisory board of former editors. Apparently, in spring 1968, that cantankerous group could not agree on a recipient. So the current editors of The Heights did it on their own — “F.X. Shea, S.J., acclaimed as Heights Man of the Year.”

“Negro talent search begins process of implementation” reported on a significant change in BC’s effort to recruit African-American students “from Boston ghettoes.” The four-person committee of BC representatives overseeing the effort added three community representatives.

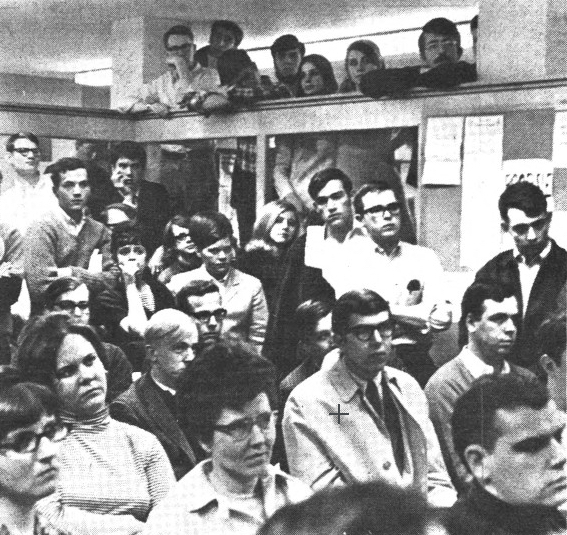

“Academic Day of Conscience opens up dialogue at BC” reported on a coordinated series of events about “the war and racism” held on campus April 24. Lectures, films, and workshops provided the content. The BC chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) joined the BC Faculty Committee for Peace in organizing the day. The student group was headed by classmates Rick Lareau and Gerry Shea. Principal speaker on the day was Prof. Howard Zinn of Boston University.

“Mastronardi sweeps field in Leonard Speech Contest” reported that classmate Michael Mastronardi won first prize for his talk on the cause and effects of white racism in American society. Classmate John Riley was second and third went to classmate Pradeep Nijhawan.

The Heights sports staff made up for the previous year by honoring classmate Jim Kavanagh — “Kavanagh named as ’68 ‘Athlete of Year.’”

In the outside world

1965

On May 2, Wagon Train ended its eight-year run on NBC and later ABC. Forty UC Berkeley students, all male, appeared before the local draft board on May 5 and burned their “draft cards,” marking the first major instance of what would become a more common event. West Germany formally established diplomatic relations with Israel on May 12. While waiting to take off on a mission May 16, a US B-57B jet bomber exploded at Bien Hoa Air Base in South Vietnam, setting off a chain reaction of explosions that destroyed 21 aircraft and killed 27 US Air Force personnel. On May 17, gas stations affiliated with the Cities Service Company changed their signage to say “Citgo.” The iconic sign in Kenmore Square was changed around that time. On May 25, Muhammad Ali knocked out Sonny Liston with a “phantom punch” in the first round in Lewiston, Maine. (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction by the Rolling Stones was released on May 27.

1966

More than 400,000 male college students took the “draft deferment examination” at colleges and universities around the country on May 14. On May 16, the albums Pet Sounds by the Beach Boys and Blonde on Blonde by Bob Dylan were released. In Northern Ireland, on May 21, the Protestant Ulster Defence Force “declared war” on the Catholic Irish Republican Army. The final episode of Perry Mason was shown on CBS on May 22, ending a nine-season run. The weekly report of US casualties in the Vietnam War for May 15-21 was a record high: 146 Americans killed and 820 wounded.

1967

Elvis Presley and Priscilla Beaulieu were married on May 1 in a brief civil ceremony at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas. In a protest against gun control, a group of 40 members of the Black Panthers, armed with rifles, shotguns, and pistols, forced their way into a May 2 session of the California Assembly in Sacramento. No violence occurred and police confiscated the weapons. There were no arrests as no state law had been broken and the weapons were returned. The Jimi Hendrix Experience made its debut May 12 with the release of the album Are You Experienced. The number of American servicemen killed in Vietnam on May 18 was 101, marking the first time more than 100 Americans were killed in a single day. At the close of the week ending May 20, a record 337 US servicemen had been killed in Vietnam that week. The weekly total also raised the overall number of Americans killed in Vietnam to more than 10,000. The aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) was christened on May 27 by the late president’s nine-year-old daughter Caroline.

1968

Representatives of the United States and North Vietnam met in Paris for the first time on May 10 to discuss peace talks. On May 12, a North Vietnamese force overran a US Army Special Forces camp at Kham Duc, shooting down an American C-130 transport plane as it was evacuating the area and killing the 156 on board. All but six aboard the plane were South Vietnamese civilians. The American nuclear-powered submarine USS Scorpion sank on May 22, 400 miles from the Azores, killing all 99 of the crew. Baseball’s National League voted on May 27 to expand to 12 teams, awarding franchises to San Diego and Montreal.